Finding shared value in public-private data initiatives.

In 1998, Al Gore, the then Vice President of the United States, delivered a speech about Digital Earth. This speech paved the way for a new business model for the data economy, where public access to information is funded through private sector business models, resulting in a ‘public good’. Digital Earth focuses on Gore’s vision of a mutually beneficial relationship between public and private sectors, not just on the private sector ‘giving back’ to society. Digital Earth aimed to create an ecosystem where data are equally accessible to all the world’s citizens, and industries can flourish by having access to a shared data source.

Over the past decade, I have worked with data in two primary industries: public health and fresh export logistics. In both cases, I have contributed to industry-level knowledge. I also serve as a board member for Shonaquip Social Enterprise, a for-profit wheelchair manufacturer supported by a community awareness not-for-profit. Their focus on holistic impact, manufacturing wheelchairs, and reaching vulnerable families with disability awareness has influenced my opinion about a new business model.

This post explores a ‘shared value’ business model (thank you, Micheal Porter) for data projects and initiatives.

Two case studies of data business models leveraging 'shared value'

Two examples of where shared value is compelling are Google Maps, being a direct representation of the Digital Earth concept, and Transport for London’s open data platform. Both initiatives follow innovative business models to deliver on their core business values. Both attribute their success to a shared value strategy—a crucial diversifier.

Google Maps as an example of Digital Earth

Google Earth and Google Maps are familiar implementations of Digital Earth. At the time of the 1998 speech by Gore, a flurry of public investment into geographical information transpired (e.g., the open-source Terra Vision TM visualisation system). Early military satellite imagery was provided in the 1990s; Google developers used this to create Google Earth. Over time, Google realised that it was dependent on this data and that it risked losing access to it. They began gathering additional sources of data, including Street View information. For those unfamiliar with Street View, Google dispatches hundreds of cars worldwide to drive through streets and captures images of the routes. Most people use Street View to explore new neighbourhoods and places. This is captured every few years; a timelapse of an area can be observed on the platform—allowing users to perceive changes to an area.

Google Maps is a daily tool for our society. We use it to find the nearest gas station or to plan our next trip. The best part is that it is free for all to use. The detailed information on Google Maps is an incredible resource. I cannot imagine a world without the amazing information on Google Maps. Some features I love the most are the shop hours, the traffic-free routes, and the histogram of the usual crowd levels of popular venues. Google hosts and calculates a massive amount of data, free for public consumption. If you work in any data processing space, you know this is a costly enterprise (not even considering the cost of maintaining thousands of cars and teams travelling each street of the globe).

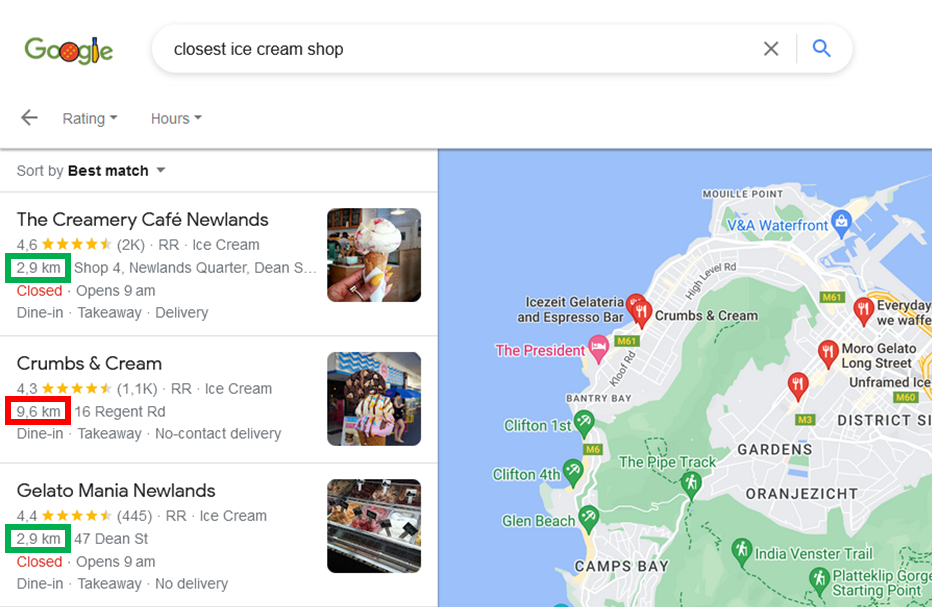

Google funds this attempt in two main ways: 1) advertising services, and 2) their vibrant application programming (API) interface for business-to-business users. Each time I Google “Closest Ice Cream Shop” (a regular search term in my history bar), Google earns revenue if I click on an option. Figure 1 demonstrates that the search results show the shops that pay for ads higher than the actual “closest ice cream shop” by default. The user can also choose to “sort by distance” after displaying the initial response. The second revenue stream is Google availing their API to other application vendors to use in-app. Business-to-business users, such as delivery services, pay for using Google Maps data (e.g., distance between locations and route suggestions).

Google Maps and Google Earth have become equalisers for citizens globally to explore the world (at least those with access to a device and the Internet). It allowed various people to explore the world and facilitated a genuine public benefit. The data behind Google Maps are primarily crowd-sourced, thanks to their network of associated services and the foundation of one or two rich data sets they funded. This resource has enabled industry development and the formation of new businesses, which is a prime example of an effective public-private partnership.

Transport for London open data policy

Transport for London (TfL) explored various options to fulfil its goal of ensuring that each journey counts in the lead-up to the 2012 Olympic Games. They manage a vast information platform and are responsible for conveying train schedules, delays, and fares to the public in a constantly evolving technological environment. TfL encountered two options: 1) provide all the information to customers, or 2) enable applications to use their data to provide a service; they chose the latter. Today, anyone can access up-to-date information on public transport journeys and timetables from their website. The data are entirely anonymised and free to use.

Transport for London (TfL) agreed on the subsequent foundations for opening access to their data:

- Security: operational data should not be tampered with and influence operations or security of platform or travellers

- Equality of access: all users should have the same level of access to data

- Reliability: the data should represent reality

- Timeous: the reality is the actual reality as of this moment, not a few seconds ago

- Unrestricted access: anyone can access the data unless legal issues present a restriction

In the years since, over 600 apps have used this open data platform to create innovative ways of delivering in-time information and services. Academics use this information to study movement patterns of urban populations, social factors, and logistical challenges. Research leads to a deeper understanding of complex problems and helps to find innovative solutions. An entire ecosystem of users, influencers, and contributors flourish because of the accessibility of this data; however, Stone, Aravopoulou and Nguyen[1] warn that institutions with similar ambitions should be wary and ensure no one can capture the market for information, with access remaining equitable.

Open Access to data—should you engage?

In both cases, Google Maps and TfL had a clear business value and an apparent public good as evidence of the success of their business models. In both instances, the company provided a product or service and facilitated the growth of a solution ecosystem; not only a ‘net positive’ but a complete overhaul in competitive business mindset, resulting in a win for public and private. The question remains: is this feasible in all industries or isolated to a handful of use cases?

Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) advocates for free access to data and information. They define open data as:

- Freely available on the Internet.

- Permits all users to download, copy, analyse, re-process, pass to software, and use for any other purpose.

- Without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from acquiring access to the Internet itself.

The benefits they believe are:

- Accelerates the pace of discovery.

- Develops the economy.

- It helps ensure we do not miss breakthroughs.

- Improves the integrity of the scientific and scholarly record.

- It is becoming recognised by several in the research community as an essential part of the research enterprise of the 21st century.

So why, if there are so numerous benefits to creating open data platforms, do we not see more projects opening access to data? The answer remains in two parts. First, creating a platform for sharing, governing, and maintaining open data is costly. Establishing a proper platform and a team to manage the platform is no small undertaking. If organic funding is available, that will be a first prize as it presents the organisation with autonomy; however, it is unusual for a company to develop in a different direction without external funding. Here, donor funding or government investment can significantly ‘bridge the gap’ for platform providers that may offer data to serve as a public good when access is granted equitably. Microsoft’s artificial intelligence (AI) for Earth initiative is an excellent example of how donor funding can drive innovation in the technology sector. This initiative benefits an investment from Microsoft’s advanced technology in sustainability AI—recipients invariably acquire a runway for projects that can have a long-term effect on society.

Second, competitive advantage can be perceived differently by various stakeholders in the ecosystem. Stakeholders can be wary of sharing data if they believe access to this data is a competitive advantage. It is natural for a private company to protect their intellectual property; however, companies using collective data resources should evaluate the factors that prevent them from investing in open data access. Governing structures significantly influence the direction of investments and can shape the development of business models that create shared value, even if they differ from the norm.

Barriers can be overcome with enough effort. The key takeaway from this article is that shared value is achievable, but it requires tenacity. A project that aims to create shared value should have clear governing principles, prioritising equality, quality, timeliness, and access.

Conclusion

To solve complicated problems, collaboration from across industry sectors is required. The digital ecosystem is a valuable way of understanding the participants using data in the industry. While funding from government or para-government institutions can often initiate opportunities, the private sector is also significant in discovering innovative business models. Collaborative public-private relationships may seem idealistic, but they can generate tangible business value. The business landscape is evolving rapidly; shared value is a business strategy that should not be overlooked. In 2023, access to data is no longer a barrier to entry, and the focus has shifted to creating shared value, particularly if it benefits an industry.

In the areas in which I work, my interest is in exploring the work of the Port of Cape Town Port Logistics Cluster. The Western Cape Government and the Cape Chamber of Commerce and Industry compel this project. In these cluster meetings, I have observed active engagement from various stakeholders, each presenting their own skills and values.

I am excited to see how data availability from all sectors can influence complex supply chain issues, and I am eager to contribute my time and skills in any way possible.